HS2 and its phases: Cnbrb, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The default British policy of ‘make do and mend’ has many infamous monuments to its discredit. Think only of the Mother of Parliaments crumbling into the Thames as report after report on its repair is kicked into the long grass, or the water companies whose failure to do their job of preventing raw sewage from polluting our waterways and coastal waters is gross enough to be visible from outer space.

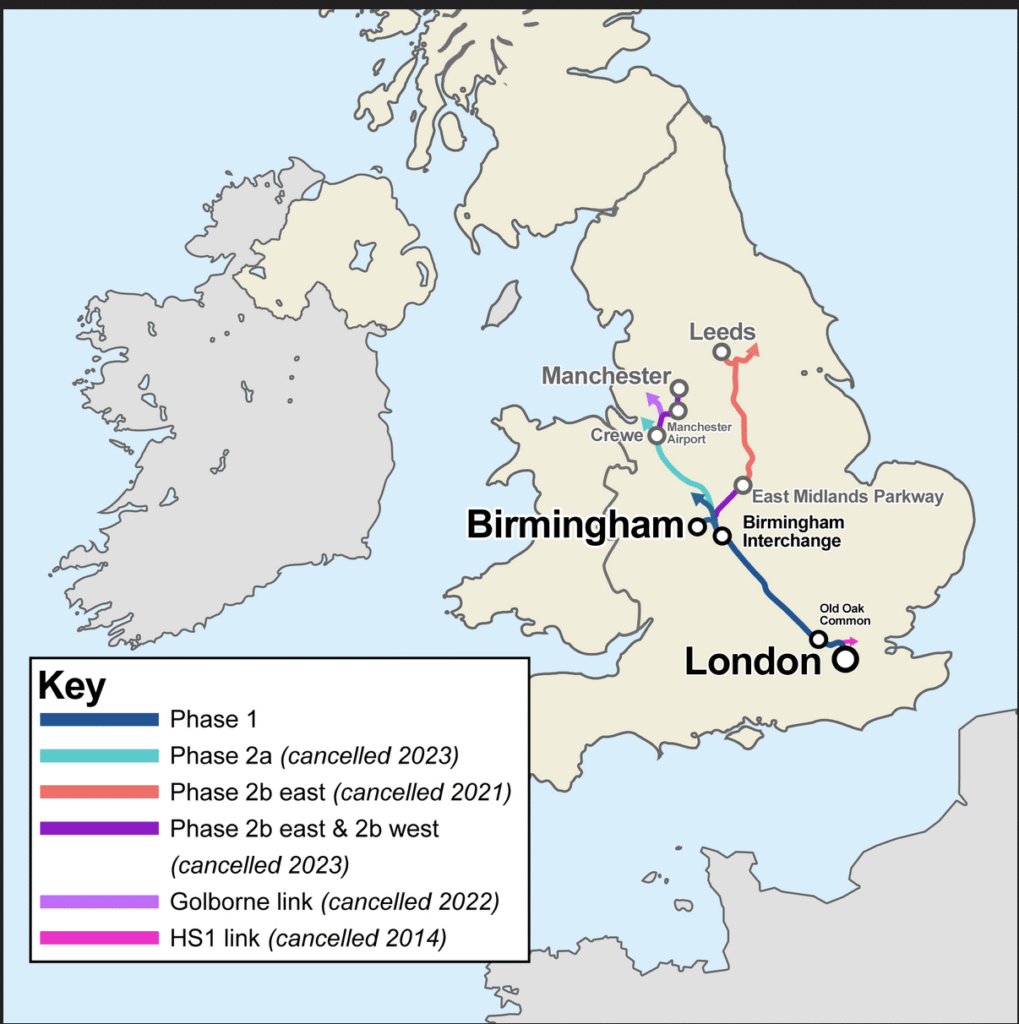

Yet bigger and far more telling of the seriousness of our multiple institutional failings than these is the debacle of High Speed 2 (HS2). Born as Europe’s biggest infrastructure project, once intended to be a vital means of rebalancing the UK’s economy with a high-speed rail line linking London with Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds, and places north, not to mention a showpiece of UK engineering, HS2 now stands as a grotesque laughing stock, exhibit A in the house of horrors of how not to execute an infrastructure project.

After 10 years construction work, following Rishi Sunak’s 2023 brutal amputation of phase 2, the Y-shaped arms stretching beyond the West Midlands, all that remains of the grand plan is the bloody stump of a fast London-to-Birmingham line, on its own justified neither by economics nor strategic national connectivity. Meanwhile, the cost of this travesty has ballooned in reverse proportion to its shrinking scope. From an original £30bn for the whole network (admittedly a heroic underestimate) the bill for completing what’s left of it has soared to nearly £70bn in today’s money – this on top of the £26bn already spent, which includes £1.7bn on the now ghosted phase 2 north of Birmingham, and £548m on the terminus at Euston, much of it wasted, for which there is no final plan, nor one in sight, which won’t be finished before 2040, and whose ambition has shrunk from being ‘world class’ to ‘serviceable’ and ‘value for money’ (even the latter being a stretch since dependent on private-sector development of the surrounding site). Hardly surprisingly, the truncated scheme is qualified by Parliament’s spending watchdog as ‘very poor value for money’, with costs now forecast to significantly outrun the benefits.

What went wrong? According to Sally Gimson, who chronicles the project’s descent into chaos in her indignant if hastily written Off the Rails: everything. First and foremost was a lack of fixed political purpose. As Gimson shows, the UK Treasury has never viewed railways as anything but a costly nuisance, rather than a strategic asset to be developed. While France, for instance, launched an ambitious electrification programme immediately after WWII and now runs an expanding TGV network, the UK still puffs forlornly behind – as Gimson notes, as Japan inaugurated its bullet train for the Tokyo Olympics in 1964, the UK was still building steam engines in Crewe, and even later putting converted Leyland buses on rails for local services. Beeching’s cuts in 1963, axing 5,000 miles and 2000 stations, were strictly about cost-cutting rather than modernisation – another wasted opportunity.

True to this tradition, when HS2 was mooted in 2009, it appeared as more an abstract exercise on which politicians imprinted a wide variety of local and personal ambitions – levelling up, showcasing engineering, greenery, regional links, local regeneration – than a transformative, once-in-a-generation national project to the direct or indirect benefit of the entire country. Thus conflicted, it disappeared from view during Brexit and Covid, which dedicated Home Counties naysayers cleverly used behind the scenes to wheedle ever more costly exceptions and modifications from ministers and departments whose attentions were elsewhere.

Political vacillation has been a recurring cause of escalating costs. Others were built in. A key reason why HS2’s costs per kilometer are eight times higher than those of countries like France and Spain lies in spectacular technical overspecification. Failing to learn the lessons of its predecessor High Speed 1 (HS1), which was delivered quickly and without drama using proven French technology, HS2 decided that its trains would be ‘the fastest, quietest, most energy-efficient high-speed trains operating anywhere in the world.’ This was not only demanding technologically; it also dramatically raised construction costs, requiring greater noise damping, stronger viaducts and bridges, and costlier track alignments and cuttings.

Weirdly, the technological overkill seems to have been driven not by technical necessity – there is none – but by finance. While the strategic case revolved around adding capacity to main-line rail links north of Birmingham, currently bursting at the seams, the economic justification depended heavily on traveller time saved, which accounted for more than 70 per cent of the calculated benefits. So, in a perfect Catch-22, to make the economics add up, HS2 needed to break speed records, which made it so hard to build it was unaffordable; but with construction so far advanced it was impossible to stop.

This inauspicious start was compounded by systematic organisational, management and governance flaws. HS2 Ltd, the government-owned project owner, already poorly staffed, had to work out how to do the biggest infrastructure project for decades at the same time as delivering it. At key points senior leadership roles were vacant – at one point the company was without a CEO for a year, partly the result of oversight from the Department for Transport (DfT) that was lackadaisical at best.

The mistakes started early. Although parliamentary approval for Phase 1 of the line was delayed from 2015 to 2017, the original 2026 opening date was inexplicably not reset. To speed up procurement, HS2 awarded high-value contracts before ground conditions were fully surveyed, leading directly to cost increases when engineering work began. Again, the civil engineering work was contracted to four international joint ventures, but lack of an overall engineering ‘guiding mind’ meant that the opportunity to standardise designs for common elements like bridges and stations — lesson No 1 from low-cost constructors Spain and France – was entirely missed. Gold-plated engineering designs from the four JVs to minimise their risk only increased the cost pressures. Not surprisingly, the parliamentary watchdog found that there was ‘not convincing evidence’ that HS2 – or civil servants, or the government – had, or even could have, the project under control.

Among too many other absurdities to mention, the most poignant section of Gimson’s book is a chapter called ‘A Disaster for Crewe’. When it was selected as a crucial hub for the new line in 2016, the Cheshire town, once the proud heart, now a sorry shadow, of the industry that the UK invented 200 years ago, could realistically see itself as a modern logistics hub ideally placed at the centre of a joined-up Britain to reverse half a century of decline. With a comprehensive overhaul of the ‘old, broken-down junction’ in the offing, the town began planning for new jobs, new homes and even a cultural centre to breathe new life into the run-down community.

All that evaporated in a puff of smoke with Sunak’s surprise announcment in 2023 – Crewe being just the largest casualty among many smaller ones on the cancelled northern arms of HS2. As well as a callous social and economic tragedy, it is a potent illustration of another unenvied UK speciality which reflects the reverse side of Boris Johnson’s slapdash cakeism: the unerring ability to to get the worst of all worlds. In this case, a hideously expensive and near valueless White Elephant of a rail line between one station that will be far too big outside Birmingham to another that doesn’t yet exist in London, using too many overengineered trains whose capacities can’t be used for what they were designed for, to the point where, scarcely credibly, service on the West Coast main line above Birmingham may actually end up worse than it is now. The Infrastructure and Projects Authority based in the Cabinet Office has one word for HS2, ‘unachievable’ – which effectively ensures that other much-needed UK infrastructure projects, in energy and water, for instance, will be quietly shunted into the already crowded siding labelled ‘make do and mend’, in the hope that they will somehow go away – anything to prevent them actually having to be built.

Simon – you put your finger on everything that is wrong about the rail infrastrucuture of this country. Grandiose ambition followed by cutbacks, stop-start projects (rail electrification being the most obvious), make do and mend with old trains, little increase in actual capacity out in the country (the hugely successful Elizabeth line being the stunning exception which shows what can be achieved). A fortnight ago I was on a double decker TGV gliding through France from Nantes to Lille which by-passed Paris on a TGV line. Yesterday I was on a South West Train from Crewkerene to Waterloo. There was a rail replacement in the middle with a bus taking us on the grossly overcrowded A303 with it bursts of dual carriageway interspersed by single lane road, which inevitably led to huge queues round places such as Stonehenge. Arriving at the station to resume our rail journey, the whole coach watched in horror as our train left without us. This seems to be modern British infrastructure.

Or take the city of Leeds, the largest West European city without a tram network or metro. Drive round the city and you see lovely wide roads out to the subiurbs on all sides with large green strips in the middle – where the trams ran until the insnae policy to kill them offv in the laate 1950s. Since then what has the City had? At least two schemes to build a new tram network that have both been axed. Then the leg of HS2 going into the city – also axed. The Beeching axe was also wielded with relish on many local lines which would have been brilliant commuter lines today (such as Wetherby to Leeds) and the local airport has no rail link at all. And all the while Leeds city centre is choked with traffic.

A century ago with the likes of brilliant engineers such as Sir Nigel Gresley the British network was the envy of the world. And yes even in the late 1980s under that great rail man Sir Bob Reid, British Rail (despite the constant negative press it received) was on the cusp of a veritable revolution. His reforms – putting a senior experienced manager in charge of each line (with responsibility for everything from the track to catering and the rolling stock) had immediate effect – productivity rose by 20% in the first year. If Reid had been able to keep going and sink the resulting savings into infrastrucuture spending (including – dare I say it – into a new line to the north but built under the waatchful eye of his tough managers) modern rail travel here would be very different. But rail privatisation aand the fragmentation of the network, the general hostility of the British public to what they have always seen as expensive travel, and what you point out the Treasury loathing of rail put paid to Reid’s reforms. A virtuous circle of productivity savings spent on infastructure to create more savings and boost demand would surely have followed.

And yet contrast that to the latest lefgof the French TGV network being built from Bordeaux south to Toulouse and a spur to Dax. Combined with a wholesale upgrade of the local rail network there to feed into the TGV, the total cost is some 15 billion euros, small beer for an extension that will be longer than the truncated HS2. And by the way it enjoys a more than helathy 87% suppoort from local residents in that neck of south west France.

Clearly what our politicians should have done when conceiving HS2 was to award the contract to one of the veteran TGV builders in France who bid to design, build and operate the section they are building on behalf of SNCF. This gives thm the incentive to keep construction costs down, innovate with new construction techniques (particularly in the very demanding work of track laying and ballast which can stand the hammering they receive from TGV operations) and an equal incentive to get the line open as quickly as possible to recoup their investment. It works a treat. It makes me weep with envy and rage in equal measure that we have never matched that – and probably never will.