To a Martian, the UK economy might appear to have plenty going for it. It has the City of London, still – just – Europe’s, and in some respects the world’s, preeminent financial centre, and the Lloyds insurance market. It has had more than half a century of bounteous North Sea oil, and from a renewables point of view its buffeting winds and sweeping tides make it a charmed location. It is big in professional services, such as accountancy and audit, consulting and advertising, and has vibrant creative industries ranging from great museums, to world-class theatre, cinema and video gaming, together producing around £124 bn of gross added value a year. Then, the UK is home to 165 universities, some of the highest global rank, to which foreign students, or at least their parents, queue up to pay exorbitant sums for an undergraduate or postgraduate degree – not to mention, and this is more to the point, more than 100 business schools, whose business courses attract 250,000 students, more than any other subject at both undergraduate and graduate level.

All of which begs a rather large question. It’s tempting just to dismiss the UK as a bullshit economy, all talk and no action. And there’s something in that. But behind that hides another and more specific question. Business is the science of action – researching, planning, implementing and managing it to eventual completion. So how can the UK have so many and well reputed institutions teaching this science to such a quantity of willing students and still make such a mess of its economic endowments (absurdly high energy costs, inability to build either houses or infrastructure, failure to generate growth anywhere outside London, Oxford and Cambridge, just for starters.)

In an interesting piece in the FT’s Business Education magazine, David Willetts puts forward some partial answers. He thinks that the UK’s overly globalist business schools put the needs of lucrative foreign students before those of domestic ones, and pay insufficient research and teaching attention to specifically UK areas of concern (admittedly a pretty wide field). He also questions the weightings used in the influential business school rankings published in the press, heavily oriented towards individual before and after salary comparisons and omitting benefits to the local economy.

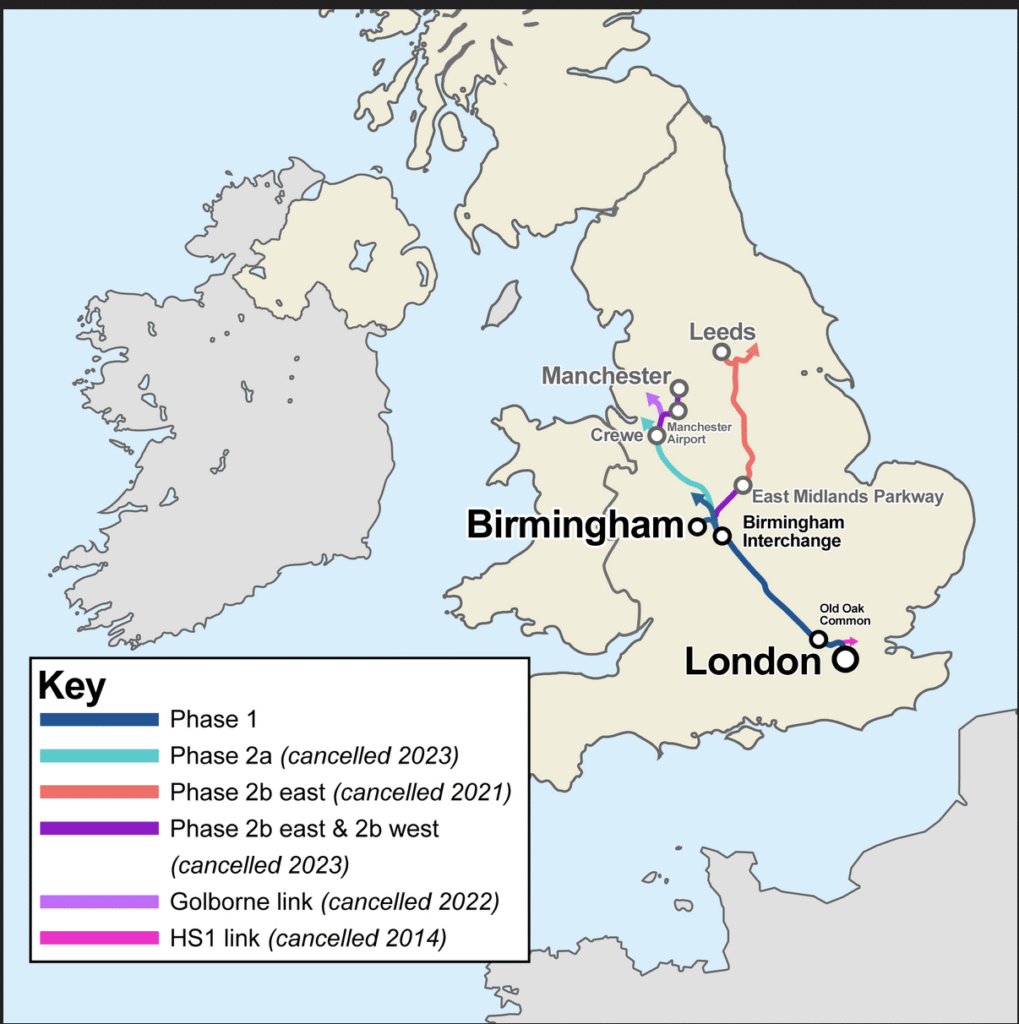

There is some truth in all this, just as there is in the idea that the UK has infuriatingly squandered many of its strengths by carelessly taking them for granted or, which comes to the same thing, leaving them to the market instead of developing them strategically. That certainly goes for energy, North Sea Oil, our transport networks and also our universities, which I have long thought to be a bubble that some day soon will pop. Our most culpably wasted strength, of course, literally tossed away, is free access to, and movement to and from, Europe, loss of which, as recent research makes clear, has caused colossal damage not just to GDP, but also to our economic dynamism. ‘The things the UK excels at, points out one recent study ‘finance and business services, tech and the creative economy, various advanced manufacturing niches – depend on openness to trade, to ideas, to skilled workers’, while its neglected provinces have never been more in need of Europe’s regional support funds.

But that still leaves the enigma of UK business education, that bulks large everywhere except in the productivity and growth figures. Many UK management courses, as Willets remarks, are fairly elementary, well below MBA level. But he overlooks a much simpler and more radical explanation for their mediocre contribution to their host country’s economy. What if, far from being an inexplicable conundrum, it is the entirely predictable consequence of teaching courses that are, um, bullshit? That what generations of business students have been learning on their expensive courses is in fact just wrong?

This diagnosis is less extreme than it might sound. LBS’s late lamented Sumantra Ghoshal began a celebrated 2005 essay, ‘Bad Management Theories are Destroying Good Management Practices’, with the observation that preventing fresh business scandals (this was post Enron, Tyco and Global Crossing), wasn’t a matter of business schools putting on a bunch of new courses, so much as stopping teaching a lot of old ones. These included governance based on agency theory, which decrees that self-interested managers must be bribed to do their job of maximising shareholder value with incentives such as stock options, organization design reflecting the need to control people’s opportunism by hierarchy and sanctions, and strategy that pits companies against their stakeholders, including society and regulators, by assuming that given the chance all of them are are out to eat everyone else’s lunch. With these gloomy and ideologically-based ideas, he concludes, business schools have conspired to create theories and practices that absolve their students from any moral responsibility for their actions and turn the daily practice of management from a force for good into a force for bad – its baleful influence all too visible in today’s grotesque wealth inequalities, the travails of an overheating planet, and the unprecedented concentration of economic and political power in the hands of a few overmighty tech oligarchs.

First, close down all the business schools, you might conclude – and you’d have my sympathy. But a more positive, and ambitious, course would be to join the courageous minority of business academics who are struggling to renew the management discipline against enormous inertia from within. When pushed, almost everyone will admit that the outcomes of today’s management practices are too grotesquely lopsided to be defensible. There are many ways to take part in the inside job of renewal, ranging from the Drucker Forum’s Next Management initiative now taking shape in Vienna and other cities, the study of the intriguing ‘positive deviant’ firms that in industry after industry appear to succeed not despite challenging sector or industry norms but because of doing so, to following in the footsteps of the systems thinkers who, like Russell Ackoff, have crossed the Rubicon to realise that ‘Problems in organisations are almost always the product of interactions of parts, never the action of a single part. Treating a single part destabilises the whole and demands more fruitless management intervention; management becomes a consumer of energy, rather than a creator’. That’s today’s UK management in a nutshell: the wheels are spinning faster and faster, but nothing is happening.

Note: Happy Christmas and an apology to patient subscribers for recent blips on the site and the delayed appearance of my recent post. The back story is that I am at present uncomfortably holed up in La Pitié Salpétrière, France’s largest hospital, with a fractured hip sustained in an accident in the Paris Metro. After an operation two weeks ago, the hip is mending and I am regaining mobility – but typing is awkward and concentration hard to maintain… I hope to get back to normal (and home) in the next month or so. As ever, thank you for your continued support and for your excellent comments.